New studies suggest that modern humans have inherited susceptibility to COVID-19 infections from Neanderthals, according to Iranian archaeologist Hamed Vahdatinasab.

“Modern humans have inherited resistance against catching a cold, and susceptibility to COVID-19 infections from Neanderthals,” ILNA quoted Vahdatinasab as saying on November 2.

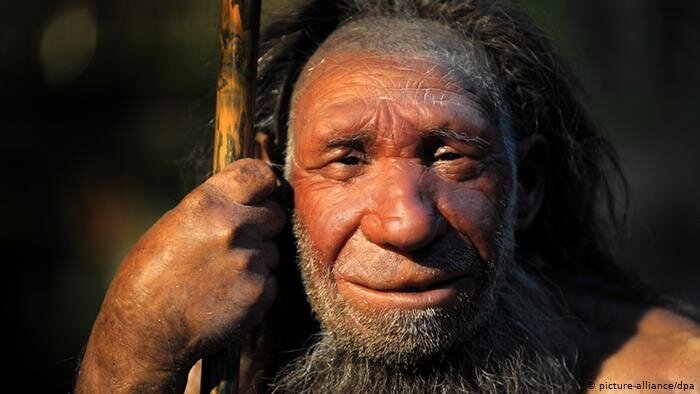

Moreover, based on discoveries Neanderthals were not primitive and savage, and they possessed the ability to talk, the archaeologist added.

“Now, contrary to our previous knowledge of Neanderthals, we know they were not the barbarians.”

“They lived in cohesive groups. They were extremely skilled hunters and knew the technology of their time. They had excellent stone tools, and they had complete control of the fire. They had body covering and footwear, and moved from place to place in pursuit of their prey,” he explained.

According to Medical News Today, in the research, the scientists found a Neanderthal gene variant on chromosome 3 that significantly increased the risk for severe COVID-19 symptoms. They found having this variant meant there was a 60% increased likelihood of being hospitalized.

“Scientists have found the variant in 16% of people from Europe and 50% of people from South Asia. Neanderthal variants are rare in Africa. In particular, the researchers found this variant in 63% of people from Bangladesh, who have double the risk of dying from COVID-19, compared with white people in the United Kingdom.”

Until the late 20th century, Neanderthals were regarded as genetically, morphologically, and behaviorally distinct from living humans. The research was led by Hugo Zeberg and Svante Paabo, scientists at Karolinska Institute in Sweden, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

“Humans migrating out of Africa were likely to be small pioneering groups and appear to have encountered Neanderthals living in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East about 60,000 years ago. As modern humans migrated out of the Middle East after encountering Neanderthals and dispersed across the globe, they carried Neanderthal DNA with them,” Medical News Today wrote.

Human evolution on the Iranian plateau

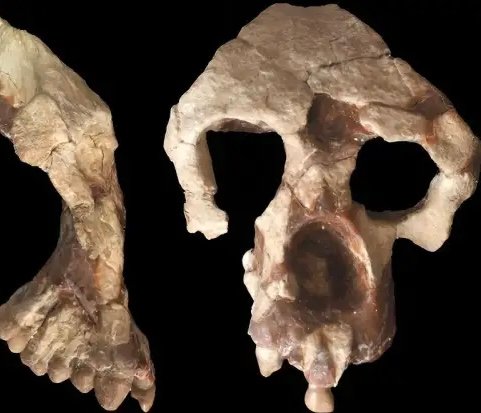

The fate of Neanderthals and their replacement by anatomically modern humans (AMH) became of greatest interest among paleoanthropologists and archaeologists. Palaeogenetics analyses have proved that AMH interbred with ancient humans including Neandertals and Denisovans. Genetic studies associated with Palaeolithic researches indicate that the last contact between AMH and Neanderthals have occurred in western Eurasia during Late Pleistocene.

A re-dating analysis of 40 sites shows that the end of Mousterian technology and most probably the disappearance of Neanderthals are not limited to specific areas, but occurred in a period between 41–39 kya in different places across Western Eurasia. Researches also suggest that a combination of climatic changes and competitive condition with AMHs extirpated Neanderthals. A key area that was outside of modern research methods for a long time, is the Zagros Mountains of the Iranian plateau, which is yielded Neanderthal remains and hundreds of their stone tools.

For instance, several surveys conducted by senior Iranian archaeologist, Saman Heydari-Guran, led to the discovery of a 42,000-year-old Neanderthal tooth along with archaeological layers embracing cultural data from Paleolithic, Middle Neolithic, and post-Paleolithic periods in and around rock shelters situated in western Iran.

The tooth, which is a lower left deciduous canine belonging to a six years old child, was found at a depth of 2.5 m from the shelter surface in association with animal bones and stone tools near Kermanshah. Stone tools discovered close to the tooth belong to the Middle Paleolithic period and a series of C14 dating suggests the Neanderthal is between 41,000-43,000 years of age which is close to the end of the Middle Paleolithic period when Neanderthal disappeared in the Zagros. Neanderthals were roaming over the Iranian Zagros Mountain sometimes between 40 to 70 thousand years ago.

Until the late 20th century, Neanderthals were regarded as genetically, morphologically, and behaviorally distinct from living humans. However, more recent discoveries about this well-preserved fossil Eurasian population have revealed an overlap between living and archaic humans.

Neanderthals lived before and during the last Ice Age of the Pleistocene in some of the most unforgiving environments ever inhabited by humans. They developed a successful culture, with a complex stone tool technology, that was based on hunting, with some scavenging and local plant collection. Their survival during tens of thousands of years of the last glaciation is a remarkable testament to human adaptation.