The historic Silk Road city of Nishapur, which is located in eastern Iran, was a place of political importance and a prosperous center of arts, crafts, philosophy and trade in medieval times.

But the city still sustains its fame today thanks to the master of arts and sciences it raised in the past: Omar Khayyam Nishapuri, or Omar Khayyam, as most Westerners know him

Inside a massive garden compound, a white marble monument of the 11th-century polymath featuring inscriptions of his poems in rhombus patterns, is one of the city’s top tourist attractions.

Nader Moradi, 30, is a frequent visitor and part-time tour guide. He called the Khayyam Garden “a second home” for him and other locals, where they gather, celebrate, grieve, play music or recite poetry.

“It’s like a spiritual retreat,” he told Anadolu Agency (AA), recounting Khayyam’s famous prophecy that he would be laid to rest where “flowers in the springtime would shed their petals over his dust.”

“Khayyam is an integral part of this city, its history, its ethos and our very identity,” said Moradi, who lives just blocks from the garden, which also houses the mausoleums of Persian mystic poet Attar Nishapuri and Imamzadeh Mahruq, believed to be among the descendants of the Muslim Prophet Muhammad.

The garden mausoleum, which represents the fusion of modern and traditional art, comes alive on special occasions, including the Iranian New Year, or Nowruz, as well as Khayyam’s birthday and the anniversary of his passing.

Popularity in Iran

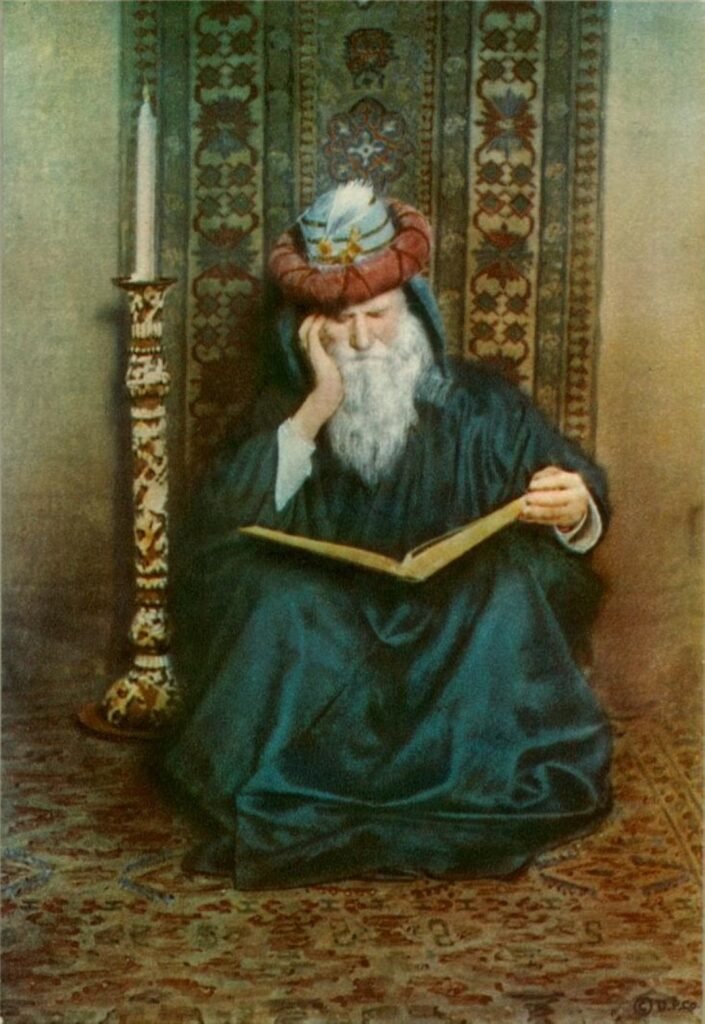

The celebrated Persian, who lived in the late 11th and early 12th century, earned fame at home and afar as a genius mathematician, astronomer and philosopher. But in the West, his chief claim to fame and stardom has been his poetry, thanks to the English translation of his rubaiyat (a collection of quatrains).

Khayyam’s groundbreaking work in mathematics and astronomy, says eminent historian and social scientist Abui Mehrizi Khormizi, catapulted him to an exalted place among his contemporaries in the East and West.

“Khayyam made stellar contributions to algebra and geometry, with seminal works to his name such as ‘Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra’,” Khormizi told AA.

Persian mathematicians like Isa Mahani in the ninth century and Mansur Khazini in the 11th century had earlier turned geometric problems into algebraic equations, but Khayyam broke new ground with his treatise on cubic equations.

“He was also the first to give the concept of Khayyam-Saccheri quadrilaterals, more than six centuries before (priest and mathematician) Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri published it in his book” in the early 1700s, said Khormizi.

There was no stopping his genius. Khayyam went on to discover what is known in Iran as the Khayyam triangle – a reworked model of French mathematician Blaise Pascal’s triangle – and even published a work on non-Euclidean geometry, Khormizi added.

As an astronomer, his major accomplishment was the invention of the Jalali calendar, commissioned by Seljuk ruler Sultan Malik-Shah I, which apparently proved to be more accurate than the Gregorian calendar developed in the late 16th century.

“Most of his astronomy-related ideas took shape during his time in Isfahan, the capital of Seljuk rulers at that time,” said Reza Wahedi, a research scholar at Shaheed Beheshti University, in Tehran, Iran’s capital.

“In Isfahan, Khayyam led a team of astronomers at an observatory that produced the Jalali calendar and made key planetary observations that find mention in his book ‘Astronomical Handbook of Khayyam’.”

Dizzying fame abroad

While German literary giant Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan, a magnum opus linking European and Persian traditions, was inspired by Persian poet Hafez, English poet Edward Fitzgerald found his inspiration in Khayyam when he translated his poetry into English in 1859.

It was Fitzgerald’s “Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam” that introduced the great Persian “astronomer-poet” to the Western world, prompting Victorian poet and critic John Ruskin to say in 1863 that he had “never read anything so glorious.”

“Despite the slow response initially, the book later caught the imagination of all and sundry in the West, giving a sneak-peek into Khayyam the poet,” said Wahedi, who considers himself a Khayyam “admirer.”

In later decades, he noted, Khayyam’s literary fan clubs emerged in major European cities and his rubaiyat made it to the Oxford Book of Quotations.

“Khayyam’s poetry, written in quatrains, revolves around the idea of ‘living in the moment’ and ‘living to the fullest,’ which perhaps appeals to the Western audience,” said Qadir Hassan Asraar, a researcher on Persian literature. “His poetry in Persian remained unmatched for many centuries.”

Khayyam’s poetry incorporates elements of philosophy as well, with a deep emphasis on feelings like hope, yearning, fear, anxieties and pleasure, said Asraar.

Almost 10 centuries since his death, Khayyam’s life and works continue to resonate widely. One example is a 1957 Hollywood biopic directed by William Dieterle named after the poet and telling his life story.

“Khayyam’s life and legacy inspire and give hope even in these gloomy times,” said Moradi. “That’s what he would like to be remembered for.”